AASP Newsletter - March 2020

Commentary on "I Was the Fastest Girl in America, Until I Joined Nike" By Lindsay Crouse

Sharon Chirban |

Jenny Conviser |

Caitlyn Hauff |

Michele Kerulis |

Riley Nickols |

Christine Selby |

AASP Eating Disorder Special Interest Group Coordinators:

Sharon Chirban, PhD, CMPC, Amplify Wellness + Performance

Jenny Conviser, PsyD, CMPC, Northwestern University/Ascend Consultation in Health Care

Caitlyn Hauff, PhD, University of South Alabama

Michele Kerulis, EdD, CMPC, Northwestern University

Christine Selby, PhD, CMPC-Emeritus, Husson University

"I Was the Fastest Girl in America, Until I Joined Nike" was published in the New York Times on Nov. 7, 2019. In the article, Cain described receiving harsh treatment from her running coach Alberto Salazar while training at the Nike Oregon Project. According to Cain, Salazar was critical of her appearance, engaged in fat-shaming, and was convinced Cain had to get “thinner, and thinner, and thinner.”

She was weighed, reprimanded, and shamed in front of other team members. In an effort to meet expectations, she lost more and more weight, all the while enduring both physical and emotional abuse and experiencing “her body breaking down.” Unfortunately, critical and shaming messages related to body and body shape are associated with increased eating disorder risk (Lie, Rø, & Bang, 2018). Cain described a plethora of resulting mental and physical health-related conditions including low body weight, amenorrhea, multiple bone fractures, relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S; Statuta, Asif & Drezner, 2017), lower confidence, fatigue, self-injury, and declining athletic performance. She felt alone, undefended, and unsupported. As a result, Cain stated that suicidal feelings began to emerge.

This story does not describe an athlete’s failure. It describes a failed system.

It describes a system that includes coaches, medical personnel, and corporate systems failing to safely inform athletes, failing to responsibly train athletes, and ultimately endangering their lives. We applaud the courage necessary for Ms. Cain to tell her story. No doubt it took her world-class skills to fight back for better conditions within the very system that abused her. But what next? Do we assign blame to a coach, the system, a corporation, or an institution and hope next time will be better?

It is understood from the Crouse report that the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) will investigate Cain’s claims. According to WADA, “Its key activities include scientific research, education, development of anti-doping capacities, and monitoring of the World Anti-Doping Code (Code)." However, this agency does not have expertise in evaluating the environmental impacts that may result in mental health issues nor in suggesting how to create healing environments.

Fundamental in credible research are the principles of reliability, validity, and objectivity. Are corporate or institutional entities who conduct research on their own athletes’ mental health, proficient in self-study and proficient in implementing plans for improvement based on results? Is WADA best equipped to study the conditions described by Cain and can they ensure reliable and valid findings?

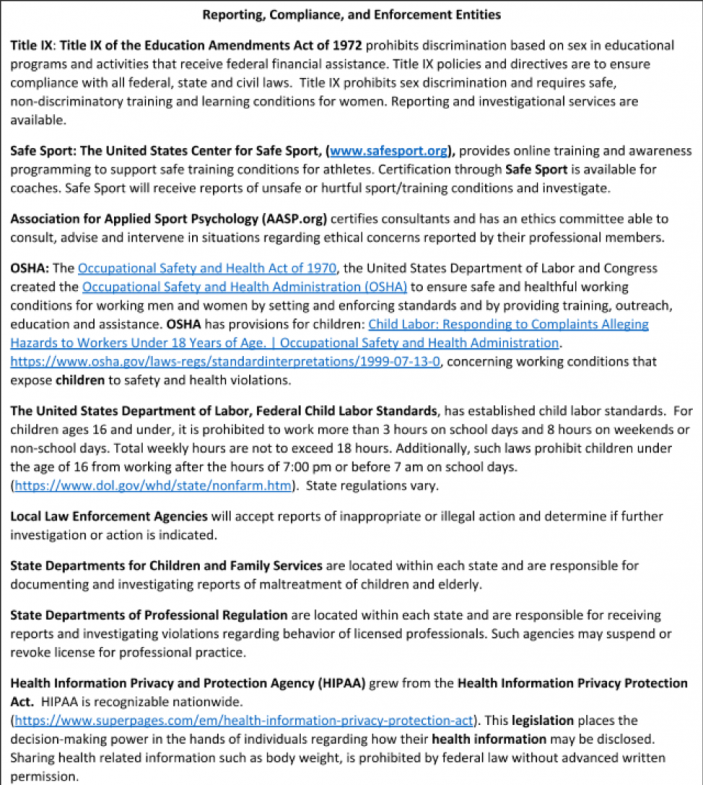

Could instituting investigations by outside entities such as Title IX, Safe Sport, Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), United States Department of Labor, Local Law Enforcement Agencies, State Boards of Professional Licensing and Regulation, State Departments of Child and Family Protective Services, or the United States Health Information Privacy and Protection Agency ensure accurate results and effective remedial action?

Unfortunately, many coaches, administrators, and training systems are the product of misinformed, outdated, and dangerous training practices. Many operate outside the parameters established by entities such as Safe Sport, American Academy of Pediatrics, and OSHA. As such, there exists the presumption from some coaches and administrators, that if they survived harsh language and grueling training strategies in their childhood, today’s athletes will survive as well. This type of thinking is misguided and ultimately harmful to athletes. Yet this message remains pervasive and especially so in elite sports.

The “more is better,” “no pain, no gain,” “quitters are losers” adages are no longer powerhouses of effective decision making or responsible athlete training.

Today's culture differs markedly from 20, 30, or 40 years ago when it was common for frustrated coaches to throw a chair across the basketball court or embark on verbal rants.

Rates of reported and observed bullying by students, teachers, coaches, and others are highly prevalent and include: Overweight: 40.8 %, 78.5 %; Sexual Orientation: 37.8 %, 78.5 %; Race/Ethnicity: 6.50 %, 45.8 %; Physical Disability: 3.30 %, 35.8 %; Family Income: .080 %, 24.9 %; Academic Ability: 9.60 %, 61.2 %; and Religion: 1.20 % 20.0 % (Puel et al., 2015). In addition, speed and quantity of data transmission and onslaught of social media exposure pose risk of perpetual emotional overload.

Youth, high school, and college athletes report high levels of stress and forgo a full night’s sleep in order to meet the demands of their academic, family, social, and sport-related responsibilities. Additionally, professional athletes worry about playing time, contract extensions, injury risk, and professional longevity. Athletes’ and coaches’ financial status are more than ever contingent on scores, wins, and potential for lucrative endorsements and sponsorships. Families can put pressure on their children to recover dollars spent. The stress experienced by family, coaches, administrators, and the athlete is communicated to each other, it interfaces with the system, and further intensifies its effect.

Another dramatic cultural change that influences the stressful sport environment is early sport specialization (ESS). ESS nets longer competitive seasons, year-round training, more out of sport adjunctive training and conditioning, longer practice sessions, and more time engaged in team or training-related travel. ESS has pigeon-holed athletes at an early age, required families to sacrifice more time and dollars for their child’s participation, and this threatens to disrupt vital psychosocial and identity development necessary for future physical and emotional health. Early specialization is a predictor of increased stress, disordered eating and eating disorders (Voelker, Petrie, Reel, & Gould, 2018).

Rates of depression, anxiety, behavioral problems, and suicide risk among children and teens are higher than documented in previous generations (5.4% in 2003, 8% in 2007, 8.4% in 2011–2012; Ghandour et al., 2019) and all commonly co-occur with eating disorders. One in six U.S. children aged 2–8 years (17.4%) had a diagnosed mental, behavioral, or developmental disorder (Ghandour et al., 2019).

Sadly, suicide rates have increased 31 percent from (10.7 to 14.0 per 100,000) over a sixteen-year period from 2001 to 2017. Suicide is now the second leading cause of death among youth and teens in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) WISQARS Leading Causes of Death Reports, 2017). Suicide was the tenth leading cause of death overall in the United States, claiming the lives of over 47,000 people with more than twice as many suicides (47,173) in the United States as there were homicides (19,510).

High levels of chronically endured stress means the “throw chair across the court” may now be the straw on the camel’s back resulting in crushed physical and emotional health. How is sport participation currently impacting our children and our families? If Nike and Salazar, previously known to be the “best of the best,” are allegedly endangering athletes, what might be the risk for other athletes in less well-funded programs or having less experienced coaches? Is this the tip of the iceberg? How many more cases like this will emerge? How many more athletes have already suffered damage?

It is not necessary to conduct another study or have additional definitive evidence that the current sport culture is, too frequently, making our children ill. It is not ethical or responsible to hide behind a veil of purported ignorance. Sports participation does not cause illness. Ill-informed training and competitive conditions increase risk of physical and mental illness. This risk is both unnecessary and negligent.

History reminds us that it is possible to reduce or eliminate risk. Different from decades ago, seatbelts are standard in all vehicles, smokers have pulled back on smoking indoors, and kids riding bikes wear helmets. It is past time for sports institutions and personnel to do their own basic training and become current in their knowledge of best practices in sport and to do so well before working with athletes of any age.

Coaches, training staff, and sport administrators demand that athletes bring their best game. It is time for coaches, institutions, and administrators to do the same.

Best practices necessary to ensure effective and safe training are:

- Yearly background checks for all administrative and sport staff.

- Training in awareness and prevention of bullying, harassment, hazing, and discrimination (including weight, body, and size-related discrimination).

- Training in the laws of mandatory reporting.

- Training and awareness programming regarding the tenets of Title IX.

- Establish limits on training time and length of season based on the child’s age.

- Limiting early age specialization and competition.

- Establish limits on weight, weighing practices, required weights, body or size shaming.

- Establish cultural change necessary to reduce eating disorder risk among athletes participating in any sport but especially in those sports having weight classes, anti-gravity activities, or body-related aesthetics.

- Appropriately trained and credentialed dietitians and therapists, sensitive to issues of gender and ethnicity and having relevant sport-related experience, training in trauma, abuse, mental illness, eating disorders, self-injury, and performance enhancement.

- Education and awareness training regarding exposure to social media and the hazards of social comparison.

- Pre-season screening for mental illness, substance use or abuse, eating disorders, trauma history, and assault or abuse. Provide ongoing treatment as indicated.

Additional Information

References

Ghandour, R. M., Sherman, L. J., Vladutiu, C. J., Ali, M. M., Lynch, S. E., Bitsko, R. H., & Blumberg, S. J. (2019). Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. Journal of Pediatrics, 206, 256-267.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

Lie, S. Ø., Rø, Ø., & Bang, L. (2018). Is bullying and teasing associated with eating disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(5), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23035

Puhl, R. M., Latner, J. D., O’Brien, K., Luedicke, J., Forhan, M., & Danielsdottir, S. (2015). Cross-national perspectives about weight-based bullying in youth: Nature, extent and remedies. Pediatric Obesity, 11(4), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12051

Statuta, S. M., Asif, I. M., & Drezner, J. A. (2017). Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(21), 1570–1571. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097700

Voelker, D. K., Petrie, T. A., Reel, J. J., & Gould, D. (2018). Frequency and psychosocial correlates of eating disorder symptomatology in male figure skaters. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(1), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1325416