Facilitating Sport Injury Related Growth (SIRG)

Published

Injury can have a drastically negative effect on athletes’ psychological well-being (Trainor et al., 2020). Initial feelings at the onset of an injury are often negative affective responses such as anxiety, denial, grief, and frustration. Many athletes describe a loss of purpose and an athletic identity crisis in which there is a loss of motivation, control and ability (Trainor et al., 2020). There is, however, a growing body of research suggesting that athletes can experience positive changes following injury (Roy-Davis et al., 2017, Trainor et al., 2020, Wadey et al., 2019). These positive changes have been associated with heightened levels of functioning socially, physically, behaviorally, and psychologically (Roy-Davis et al., 2017). The term given to this positive change phenomenon is Sport Injury-Related Growth (SIRG).

HOW TO ACHIEVE SIRG

Sport injury-related growth is defined as the “perceived changes that propel injured athletes to a higher level of functioning” (p. 36) than was present prior to the injury (Roy-Davis et al., 2017). An athlete’s perspective can and will shift throughout their injury experience. For example: I tore every ligament in my knee during my senior year of collegiate soccer. Throughout the process of surgery and rehabilitation of my knee I was constantly told where I should be progressing and how I should be feeling, rather than coming to those conclusions on my own. The immediate response to injury is typically negative, and over time may become more positive, so it is important athletes have the chance to process these emotions in their own time. There is no “one size fits all” approach when it comes to an injury experience and thus no specific timeline to determine how long it will take an athlete to decide they are ready to move forward. It has taken much personal reflection, and physical adjustment for me to come to the understanding that through my injury, I was able to grow outside of only my “athlete identity,” recognize other passions and pursue my current career path. When I began viewing my injury as having been a learning and growing experience, I began engaging in SIRG.

Athletes can determine the narrative of their injury through reflection of the injury itself, their emotional response to the injury, and how that experience has shaped subsequent life events and/or athletic goals. Ways to reflect on the injury experience may include discussions with a coach or athletic trainer, as well as assessment of current emotional/physical states compared to where those states were in the immediate aftermath of the injury. Appraising the injury as a learning experience has been shown to strengthen psychological well-being and self-efficacy (Trainor et al., 2020). To facilitate SIRG, it is important that athletes appraise the adversity they face as a challenge.

APPLIED IMPLICATIONS

Key Applications for Athletes Looking to Achieve SIRG:

1. Share your injury experience with a coach, athletic trainer or sport psychology practitioner (Wadey et al., 2019).

The benefit of sharing your injury experience and how it shaped your perspective is that it will leave room for a sport professional to challenge, contextualize and reconstruct that perspective as having been an opportunity for growth (Wadey et al., 2019).

2. Remember that injury recovery and SIRG are not linear processes.

After returning to sport, some athletes have engaged in SIRG through viewing their injury recovery as an opportunity to gain resilience and a greater appreciation for sport and health, but this is not always the case (Trainor et al., 2020). In other words, while SIRG is important and should be celebrated, athletes should still feel comfortable in sharing the ongoing challenges and adversity that accompany their injury recovery process.

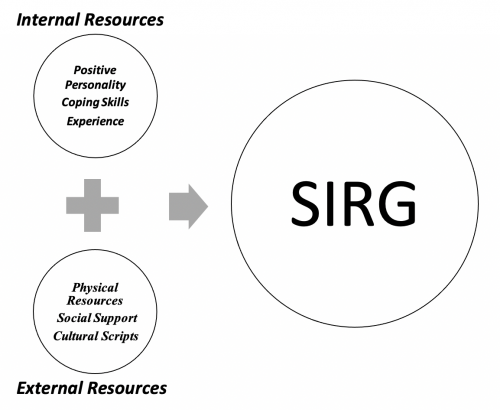

3. SIRG is dependent on availability/access to internal and external resources (Roy-Davis et al., 2017).

Achieving SIRG relies heavily on available resources (see Figure 1). Athletes can adapt internal resources (i.e., awareness of effective social support, adopting optimism and recognizing typical response to stress as ways to challenge negative thoughts and foster positive emotional/behavioral responses) to better reflect those that have been shown to facilitate SIRG and use external resources (i.e., access to narratives of successful recovery outcomes within sport culture, access to rehabilitation equipment, emotional and tangible social support, and/or time to pursue interests outside of sport) as a means to support available internal factors (Roy-Davis et al., 2017). Some internal/external resources may be relied upon more than others, and an athlete does not need to have access to all of these resources to achieve SIRG. It is important for athletes to know that their internal resources can be adapted and worked on, to aide in injury recovery/facilitating positive growth, and external resources can be used, when available, to support the changes made to internal resources.

4. Seek Support

Injured athletes can seek support from qualified practitioners (e.g., sport psychologists) who have the ability to encourage, ask questions, open lines of communication to social support and remind the athlete of their ‘why’ in sport and life (Wadey et al., 2019).

CONCLUSION

Injury creates ongoing strain physically and psychologically for an athlete. SIRG relates to an athlete’s ability to positively reappraise his/her injury experience. Specifically, SIRG is the perceived positive changes an athlete can experience following a sport injury (Roy-Davis et al., 2017). SIRG can be achieved once an athlete reaches a stage of expansion of the self, under which they have acknowledged the adversity and negative side effects of their injury and are ready to move on (Trainor et al., 2020). It is important that the athlete come to this realization in the time needed, and not feel rushed by outside factors such as coaches or parents dictating a “timeline” of how long it should take to emotionally recover from an injury. To best facilitate SIRG athletes need to positively reappraise their injury as a learning experience and reflect on the experience to determine how they were able to cope and overcome this obstacle to performance. Athletes can work towards reappraisal of their injury by sharing their story and seeking support from practitioners who can help to identify and label the growth and opportunities that have come as a result of that injury experience.

Figure 1. Internal and External resources related to SIRG (see Roy-Davis et al., 2017).

Ex: Prior experience with an injury and knowledge of the outcome + support from family/teammates/friends will provide a better opportunity for that athlete to achieve SIRG.

References

Roy-Davis, K., Wadey, R., & Evans, L. (2017). A Grounded Theory of Sport Injury-Related Growth. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 6(1), 35-52.

Trainor, L. R., Crocker, P. R. E., Bundon, A., & Ferguson, L. (2020). The rebalancing act: Injured varsity women athletes’ experiences of global and sport psychological

well-being. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 49, 1-10.

Wadey, R., Roy-Davis, K., Evans, L., Howells, K., Salim, J., & Diss, C. (2019). Sport psychology consultants’ perspectives on facilitating sport-injury-related growth. The Sport Psychologist, 33(3), 244–255.

Share this article:

Published in: