Sport, Race, and Social Justice: Honoring Black Athlete-Activism

Published

The Dual Role of Athlete and Activist

The arena of sport and performance is often regarded as a utopian space where, unlike other facets of society, equity and cultural acceptance are assumed to be the norm. However prevailing or idealistic this notion may be, in truth, this does not reflect the reality for some athletes. Throughout history and in recent times, athletes have faced social and cultural injustices within their sport while simultaneously navigating similar challenges within the larger society. Black athletes have frequently served in the dual roles of athlete and activist, balancing both the expectations to “just play” and attain performance excellence while also exercising their right to speak up about systems, policies, and unspoken practices that create an uneven playing field, or on a larger scale, a biased and unjust society. Therefore, in honor of Black History Month, we wanted to pause and reflect on the ways in which Black athletes have navigated the intersections between race, sport, and social justice, highlight some of the accomplishments they achieved while doing so, and provide steps we can take to follow in their footsteps

The Black Athlete-Activist

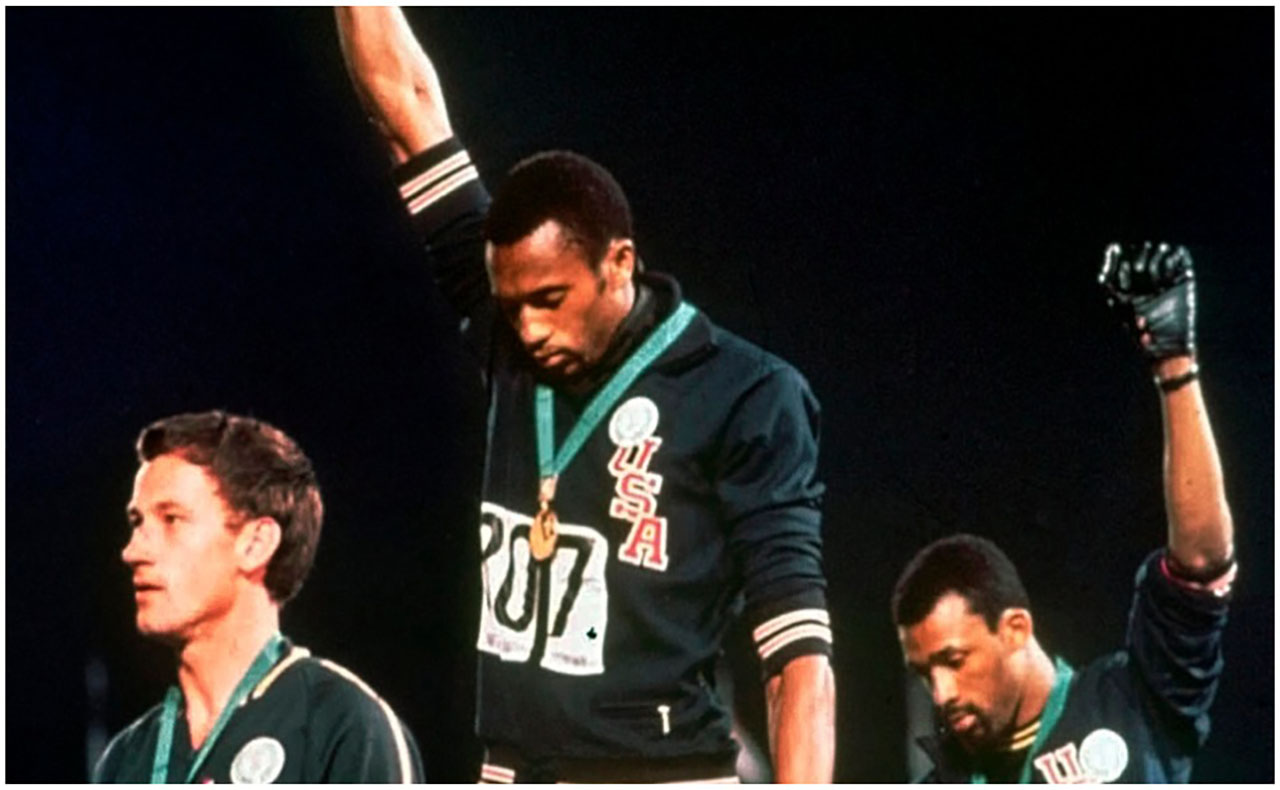

In order to better understand the nexus of Black athlete-activist, we should note a few athletes and historical incidents that helped to define it. After winning gold and bronze medals in the 200m race at the 1968 Mexico City Olympic games, USA track and field athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised a gloved-fist to symbolize the struggle for human rights in a year marked tragically by the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert Kennedy. Both were ostracized and berated for their actions upon their return home. In 2010, Hall of Fame basketball player Bill Russell received the Medal of Freedom for his work on civil rights. Russell participated in the 1963 March on Washington, conducted integrated basketball clinics in Jackson, Mississippi, and was an outspoken critic of segregation. The death of Muhammad Ali in 2016 re-ignited a critical imagination of a time when Black men were expected to fight for country while being denied civility and civil rights at home. Ali’s refusal to serve in the Vietnam War became a defining historical moment for the Black athlete-advocate. Other athletes like Jack Johnson, Jesse Owens, Althea Gibson, Wilma Rudolph, and Jackie Robinson faced racism and discrimination in sport and were silenced. Despite this, their courage and resilience opened doors for Black athletes to speak out against social injustice today. The photograph of the Miami Heat in hoodies, NBA players wearing “I Can’t Breathe” t-shirts, and Kaepernick’s taking a knee during the national anthem represent some of the modern ways Black athletes have used their respective platforms in sport to draw attention to the cultural illusion of meritocracy in America.

Call to Action

As members of the sport and performance community, we have to do more than intellectualize the possibility of bringing about social justice. We have to work for sport to be(come) a space where equity and equality co-exist. The future of sport (and society) cannot afford for us to be paralyzed. Yet, we may wonder, “what can I do” or “where can I begin?” Collective advocacy always begins with us. It can have far reaching influence - even with small steps. Here are three simple strategies for moving towards social justice in sport:

1) Read.

Regardless of our own personal and social identities, we all benefit from better educating ourselves on historic and present-day racism in sport. Doing so provides us with the knowledge and language necessary for action. Consider reading the following:

- 40 Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete (2006)

- Days of Grace: A Memoir (1994)

- Sport and the Color Line: Black Athletes and Race Relations in 20th Century America (2004)

- Sport, Racism and Social Media (2014)

- The Importance of Athlete Activists (2015)

- There's No Race on the Playing Field: Perceptions of Racial Discrimination Among White and Black Athletes (2003)

2) Reflect.

Examine your personal values, prejudices, and biases about sport. Making sport more equitable means rethinking our daily practices. We might start by reflecting on how we view athletes of various races, genders, abilities, and socioeconomic statuses in the context of competition and performance. How might our values, biases, and prejudices lead to discriminatory or exclusionary practices that limit opportunity or access to sport?

3) Speak up.

Have you ever heard a derogatory comment directed towards an athlete of color or any marginalized member of society and not acknowledged it? Decide to say something, engage in difficult dialogues (Souza, 2012), and challenge inequality. Speak with athletes, coaches, colleagues, and clients about racism. Acknowledge that it exists and influences our daily experiences.

In honor of the courageous Black athletes who fought for the right to compete, overcame taunts and threats of violence, as well as risked their careers and lives for social issues and equality, commit yourself (at minimum) to reading, reflecting, and speaking up. Think of Arthur Ashe’s statement of “Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can.” as calls to action, because whatever you do, know that each act (and inaction) matters to the future of sport and society.

References

Abdul-Jabar, K. (2015). The Importance of Athlete Activists. Time. Retrieved from http://time.com/4114002/kareem-abdul-jabbar-athlete-activists/.

Ashe, A. and Rampersad, A. (1994). Days of Grace: A memoir. New York: Random House, Inc.

Brown, T.N., Jackson, J.S., Brown, K.T., Sellers, R.M., Keiper, S. and Manuel, W.J. (2003). There's no race on the playing field: Perceptions of racial discrimination among white and black athletes. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 27(2), 162-183.

Farrington, N., Hall, L., Kilvington, D., Price, J. and Saeed, A. (2014). Sport, racism and social media. New York: Routledge.

Miller, P., and Wiggins, D. (2004). Sport and the color line: Black athletes and race relations in twentieth-century America. New York: Routledge.

Rhoden, W. (2006). Forty million dollar slaves: The rise, fall and redemption of the black athlete. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Souza, T.J. (2012).Facilitating difficult dialogues in the classroom [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www2.humboldt.edu/diversity/sites/default/files/Difficult_Dialogues_Souza_Presentation_Slides.pdf.

For more information about AASP’s diversity initiatives and resources, please check out our website.

Share this article:

Published in: